Subversion of the mainstream is a crucial tool in the development of an internal spirit of resistance to the normalities of mass cultural ideologies that fuel complacency and/or aversion of critical issues by the populace. Deconstructing familiar modes of representation and expression found in mainstream media, and reconstructing and recontextualizing visual and auditory/linguistic information, is a method by which artists have succeeded in creating works of art that are intuitively accessible by larger numbers of persons, both within and outside of the art world. Familiarized structures of communication are significant tools for the subliminal transfer of cultural self-criticism through artworks, such as those created by the artists Martha Rosler, Bjørn Melhus, and Kenneth Moylan.

Bjørn Melhus is a new media artist who is knowledgeable of and exploits the tactics of commercial marketing and mass psychological influence mechanics, such as rhetoric found in news, politics, Hollywood, talk shows, and televangelism. His work is a personal critique on what is going on in the media world, using solely appropriated sound material from mass culture, and lending his body and face as the work’s consistent protagonist over many years. He relies on the affectivity of the appropriated material, while reconstructing and supplementing its visual structure: translating visual modes of communication and reframing gleaned auditory fragments perform an act of subversion of the standardized, conformative informational construction from which we have sprung, and under which we collectively operate.

For his 2001 piece Weeping, Melhus selected small fragments of speech from the Trinity Broadcasting Network, and masterfully constructed a sonic art work from under twenty snippets of sentences of various program hosts. From the short, decontextualized phrases, the artist forms an alternative syntax and employs several ingenious tactics to work the emotions of the audience, causing an increase of anxiety as the work progresses. The installation consists solely of two large vertically rectangular screens from which emanate a pulsating, gloriously bright yellow field of color, the edges slightly darkened to a rich orange. The speakers hum heavily and maintain a constant vibration within the room, mimicking the majestic undulation on the screen, from which finally emerges two nearly identical male portraitures, staring sternly as they become visible from the center of their halos.

Maintaining their intent gaze, the figure on the left screen finally breaks out and speaks, his voice unnaturally high pitched, “I want you to know that we have seen,” and returns to stillness, his stern gazed recomposed. After some seconds pass, the same figure repeats himself, while the figure on the right hand side stares unflinchingly into the audience, his expression slightly more tense than his counter-speaker on the left, who continues to repeat this phrase, maintaining composure, pitch, and speed, while shortening the intervals between each redundant announcement. Finally upon the eighth utterance, we are fully confronted by both portraits, reciting in unison what we are waiting to break away from, the same phrase, “I want you to know that we have seen,” immediately followed by the chorus of a calm yet threatening declaration, “Blow the trumpets.”

The talking heads continue, alternating and in unison, reciting fragments meant to incite an emotional response, aided by the emergence of a subtle yet poignant and significant beat of a cymbal behind the spoken text. The portraits speak with increasing urgency, yet never alter their facial expressions, and never break their gaze with a blink. The unnatural maintenance of the facial image and gaze under the glow of such warm and alarming colors gives the digital discourse an otherworldly quality, one which is severely foreboding. Alternating in speech, they repeat one another, finish each other’s constructed sentences, and respond to one another. Back and forth they recite their sound bites: “If you stay” / “Instead of getting discouraged” / “If you stay” / “To experience what your heart yearns for.” The tension rises as the left side portrait pleads in opposition, “I can’t do this!” to the stern-right’s repeated projection “if you stay…”

The language’s history as fragments of a televangelist preacher’s speech makes itself apparent through the voice’s tone and inflection, and enhanced by the majestic glow of the portrait’s shroud of color. The snippets of religious rhetoric are heavy and carry the burden of a lengthy sermon in their few words, offering a blunt, yet somehow elusive, criticism of power and exploitation: “There is a dark empty place, with power. Something, with power. Something, in between the sacrificed. In between the sacrificed, there is a dark empty place.” Finally, having built within the spectator a weighted sense of impending disaster or struggle, the double-image plea ds with the audience for an unbridled resistance: “Instead of getting discouraged, you start crying a little louder … Instead of giving up, you will begin to cry out and groan and moan, in groaning so deep for utterance, until you hit rock bottom in the spirit,” and the right side figure ends the piece with a wide-eyed straining push to let the last words escape, “with human performance, or with human machination, gets ready to impregnate his people with the seed of glory, weeping, weeping, weeping, weeping…”

ds with the audience for an unbridled resistance: “Instead of getting discouraged, you start crying a little louder … Instead of giving up, you will begin to cry out and groan and moan, in groaning so deep for utterance, until you hit rock bottom in the spirit,” and the right side figure ends the piece with a wide-eyed straining push to let the last words escape, “with human performance, or with human machination, gets ready to impregnate his people with the seed of glory, weeping, weeping, weeping, weeping…”

This piece uses the disembodied portrait structure that we find in news and politics, and infuses this structure with a collage of linguistic sign processes, decontextualized and reformulated to beg critique of the language itself, its meaning, as well as the very facialized structure through which we receive the communiqué. In his book New Philosophy for New Media, theorist Mark Hansen addresses the nature of the digital facial image in new media art works, stating that the encounter of the digitally constructed facial close-up functions as “the medium for the interface between the domain of digital information and the embodied human that you are.”[1] In our response to digitization, we construct an image of human embodiment within the virtual realm, which personalizes the technology and provides a comfortable interface for human-machine interaction. The standardization of media culture and communication has been made personably accessible by the construction of this facialized mode of direct-address, where the sincere talking heads of the digitized world look in our eyes and speak directly to us.

The use of the visage in mass media comments to the reinvestment of the body as a precondition for communication. This embodied approach to digital media provides us with a much more grounded standpoint from which to approach the media message. The subversion of the familiarized structure of the cropped, stern digital facial image, that is the ominous and anonymous de-bodied visage of the televised world, is an effective method by which Bjørn Melhus makes his critique intuitively available to his audience. This is the structure through which we understand our world, through the gaze of a humanized collection of colored pixels on our television sets. Mass culture delivered to us through the words and lips of the floating head in our living rooms, now appropriated, condensed, reordered, and regurgitated and thrown back into a parody of its previous existence: the mimic.

In a more recent work, Deadly Storms (2008), Melhus appropriates sound bites from FoxNews to construct paradoxical and ironic statements that exemplify the culture of fear the station perpetuates. As always, he lends himself as the work’s protagonist, with three nearly identical portraits of himself on three screens. He is hairless and shirtless, as if he were an anonymous mannequin ready to t ake on any identity. Behind the three portraits, we are distracted by floating and soaring orbs of color; beneath the figures is a band of pulsating gold color with constantly changing texture, intended to mimic the news ticker at the bottom of the news screen. Using the very same methods as in his piece Weeping, Melhus reconstructs a narrative with fragments of mainstream news reporting to reveal the mechanisms of their rhetoric.

ake on any identity. Behind the three portraits, we are distracted by floating and soaring orbs of color; beneath the figures is a band of pulsating gold color with constantly changing texture, intended to mimic the news ticker at the bottom of the news screen. Using the very same methods as in his piece Weeping, Melhus reconstructs a narrative with fragments of mainstream news reporting to reveal the mechanisms of their rhetoric.

As suggested by Manon Slome in the writing for the exhibition Aesthetics of Terror, there is “the emergence of an artistic sensibility that has been informed by the imagery and politics of terrorism in the current culture as they have been formulated and conveyed through the popular media. Artworks might imitate or mirror this media rhetoric, identify its mechanisms to the viewer, critique it, push back or protest against it” [2]. This is precisely what Melhus accomplishes in this work; by taking only fragments of speak from news anchors on a decidedly right-wing news station and reording them into contradictory and repetitive statements, he successfully identifies and critiques the mechanics of mainstream cultural rhetoric to the viewer.

When considering the concept of subversion of familiarized structures as a method of transmission of points for cultural criticism and intuitive introspection, one will find insightful theory and practice through the investigation of the writing and multimedia artwork of Martha Rosler. The politicization of Rosler’s work stems from her desire to explore possible explanations of the world that she finds elusive or nonexistent in mainstream culture and media, and which are “crucial to its understanding,” and her belief “that there are always things to be told that are obscured by the prevailing stories.” [3] Her work throughout the decades can be characterized by the constant element of cultural critique, focused on quotidian American life, primarily that of the white upper-middle class persuasion, and the relationship of Western leisure and consumerism to the ongoing wars throughout the world, specifically those in which the United States has had a significant role.

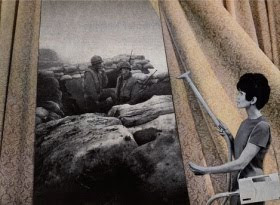

Rosler’s series Bringing the War Home (1967-72), focusing on the Vietnam War, and the more recent extension of the project, Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful (2004-2008), are photomontages that become immediately subversive of all forms and elements employed in their construction. The familiarized structure that Rosler employs in these images is that of the interior, domestic space, one which is both somehow idealized and sterile. These interior spaces of leisure and safety are contrasted sharply with the juxtaposition of war imagery in and beyond the projected internal home-space.

In some images, such as Balloons of the first series, Rosler takes the familiar domestic space, as represented by our mass media machine in home décor magazines, and thoughtfully inserts figurative elements from other sources, such as Life magazine, where documentation of war horror depicts the mangled bodies and anguished faces of foreign victims. In Balloons, the interior space seems to be of part of a clean, white staircase, behind which we see a living room, with glass coffee table, and a bundle of colored balloons, suggesting the festivities of a child’s birthday celebration. In the stairwell, Rosler has collaged the image of a Vietnamese man, with an obvious expression of severe distress, carrying the limp, and perhaps deceased, body of a young child. The tension created by the man’s expression, composure, and gesture in the stark whiteness of the  American middle-class home is irreconcilable.

American middle-class home is irreconcilable.

Rosler appropriates imagery from mass media, and, like Bjørn Melhus, collages fragments of our media reality, and uses understandable structures through which to translate these reconstructed snippets, to further subvert and reclaim the power that these mechanisms harbor. Her work is a serious investigation into the deconstruction of cultural consciousness, as organized mass media: “…I use a variety of different forms, most of which are borrowed from common culture, … Using these forms provides an element of familiarity and also signals my interest in real-world concerns, as well as giving me the chance to take on those cultural forms, to interrogate them, so to speak, about their meaning within society.” [4]

In another piece of the Bringing the War Home series (1967-72), Cleaning the Drapes, the artist has chosen an image of a white female, with vacuum in hand, as the title suggests, cleaning the drapes. Her expression is somewhat blank as she looks past the drapes, through what we would assume is the glass window from the interior of her home-s pace, out into a fairly close landscape scene composed of large boulder rocks, behind which are situated two soldiers, fully uniformed, with weaponry, but standing calmly. This image bluntly juxtaposes the domesticated female figure with the heavily clad soldiers who make her life possible; placing these men outside of her window, so that as she completes her household chores she can gaze upon their field work, creates a tension that begs the viewers to question their own relationship to their interior, domestic space, and the world from which it shields them. What if, from the unscathed glass of our window, we were to see the force of military occupation and the destruction of the land and homes of innocent families?

pace, out into a fairly close landscape scene composed of large boulder rocks, behind which are situated two soldiers, fully uniformed, with weaponry, but standing calmly. This image bluntly juxtaposes the domesticated female figure with the heavily clad soldiers who make her life possible; placing these men outside of her window, so that as she completes her household chores she can gaze upon their field work, creates a tension that begs the viewers to question their own relationship to their interior, domestic space, and the world from which it shields them. What if, from the unscathed glass of our window, we were to see the force of military occupation and the destruction of the land and homes of innocent families?

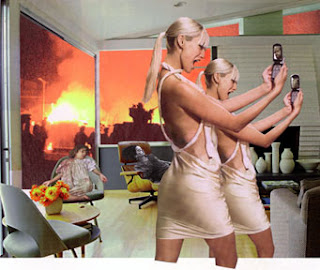

The horrors of war represented in media are far from us, a place we cannot even imagine or comprehend, we have no starting point from which to begin to perceive the realities of terror (the State makes sure of this). Within the same constructs we find presentations of the horrific unknown, we are inculcated with the ideals of what our lives should be: commodified, glorified, consumed. From the more recent series of Bringing the War Home (2004), the work Photo-op is for egrounded by the double-imaged figure of a thin, white, blonde-haired female holding a cellular telephone with camera capabilities. She holds herself in a wide-legged, twisted stance, her mouth open with an expression of extreme enthusiasm. Behind her, to the left, we see the limp and mangled body of a small female child, cross-legged and lifeless in a white, modern chair. The child’s face hangs to the right, directing our gaze, and we notice, just behind the foregrounding model, the black-and-grey charred suggestion of a figure: a carcass cradled by the common home’s office chair. Through the large window panes of this interior space is a vibrant array of yellow and orange, illuminating billows of smoke and the silhouettes of figures and military tanks.

egrounded by the double-imaged figure of a thin, white, blonde-haired female holding a cellular telephone with camera capabilities. She holds herself in a wide-legged, twisted stance, her mouth open with an expression of extreme enthusiasm. Behind her, to the left, we see the limp and mangled body of a small female child, cross-legged and lifeless in a white, modern chair. The child’s face hangs to the right, directing our gaze, and we notice, just behind the foregrounding model, the black-and-grey charred suggestion of a figure: a carcass cradled by the common home’s office chair. Through the large window panes of this interior space is a vibrant array of yellow and orange, illuminating billows of smoke and the silhouettes of figures and military tanks.

In this image, Rosler crudely smashes together the glorified images of materialist culture with the hyper-real representations of the Iraqi war. Subverting mainstream structures of commercialized spaces and infusing them with fragments of mass cultural content (models, commodities, furniture, disfigured war victims), Rosler critiques the realism of our represented and lived realities. She gives the audience an entry point into this criticism through her use of familiarized structures (the common domestic space) and implores her spectators to question the legitimacy of these very constructions: referring to the war images, “Their precise positioning, into rectangular windows and picture frames, is less a design than a visual clue to the cognitive connection Rosler is making; these images of war are not imposed or forced into these living room, they belong here.” [6]

The issue of realism is a significant one within these series, as Rosler strives to construct a space that is believable and accessible. She seeks to formulate a coherent space, where the marriage of opposing and distant realities can communicate an honest concern for the necessity to fully comprehend the direct relationship between them: “In all these works, it was important that the space itself appear rational and possible; this was my version of this world picture as a coherent space—‘a place.’” [7] The appropriated war images from mass culture are highly emotionally charged, meant to incite strong emotions of sadness, sympathy, and fear. By altering, cropping, and rearranging segments of these images and placing them into safe and sterile environments, she both neutralizes and recharges them: “Rosler’s principle of montage also required the creation of the illusion of a coherent new physical space, simplifying and rationalizing the image structure and lowering the emotional temperature from hot to cool.” [8]

Another artist working in collage, Kenneth Moylan intuitively formulates images that are comprised of a variety of elements, moving back and forth between perspective and culture. Like Martha Rosler, Moylan finds his source imagery in mainstream culture (in fact, they both use the ironically titled Life magazine as an image source), both contemporary and historical. In his collage works, Moylan is similarly concerned with the seamless construction of a realistic space, masterfully editing light and tone, and pairing texture to allow the viewer’s eye to move across spatial perspectives with tremendous ease. He describes his work as “diaristic,” an exploration into the self through fragments of appropriated and altered culture. [9]

In the work Sand Surfing, of the Actualities 2 series, we are first taken by the bright, smiling face of a white, blonde-haired female who is leaning back and clutching onto what seems to be a sled-like bowl form. She rests upon the highly saturated representation of sand; her composure and the title of the work both suggest to us a moment of leisure, an enjoyable weekend recreational activity. Upon the very tip of the mound on which this amiable figure glides, there stands a nude male figure, whose dark skin stands in sharp contrast to the lightness of the woman’s skin, the clean, sterile whiteness of her slacks, and the hazy blue and green atmospheric background that is placed above and behind the sandscape. The male’s figure has his back to use, and we see the clenched muscles of his buttocks and the strong, articulated curve of his back as he holds his bow and arrow taught, aiming to the left, beyond the frame of the image, ready to shoot at his prey. His posture and appearance suggest necessity: he is hunting for food. He is not playing bows and arrows to pass the time, but must engage in labor to acquire food. As you move up the image, his figure nearly disappears as the background transforms into a depiction of a middle-cl ass 1960’s living room. The multicolored furniture, neatly arranged, and the various floral and artistic decorations around the room return the image to a sense of comfort and

ass 1960’s living room. The multicolored furniture, neatly arranged, and the various floral and artistic decorations around the room return the image to a sense of comfort and

Moylan employs the same strategies of transmission as Rosler and Melhus by imposing alternative variables onto a familiarized structure: sandwiching the “other” between two normalities, this work begs the audience to question our understanding of the relationship between the standardized home-space and the foreign. What does it mean to have the time for leisure and recreation, to have a decorated, pristine, and empty domestic space? What is the implication of the possible fetishization of the foreign with native art upon the walls, the mish-mash of learned and appropriated culture and heritage? This work has an obvious tension, one that explores the dichotomies between leisure and necessity, recreation and labor, “white” and “black”, the privileged and the exploited, the advanced and the left behind.

In comparison with Rosler’s piece Photo-op, one can see immediate similarities; however, the mood of the two works is very different; Moylan’s work is far more subtle and intuitive. His artwork is a careful documentation of an introspective process, one that yields provoking imagery whose weighted meaning seeps in almost without notice. Both artists, whether analytically or emotionally, are working through similar issues regarding the Western reality of materialism, vanity, and leisure. While Rosler’s work is more direct and, in some ways, aggressive, Moylan creates images that surprise and confuse. As if they were a visual documentation of a Freudian slip, his images emerge and recede in profound ways.

Another work by Moylan, entitled The Flood, is comprised of solely three elements of collage: the multicolored and highly texturized “flooring” of what could be an oil spill (the foreground and bulk of the image), the counter space of a 1970’s kitchen, and the hardly noticeable snippets of outdoor foliage that appear as the background beyond the kitchen’s walls. There is a stark c ontrast between the tones and textures of the two main elements of this work: the structure of the kitchen and the organics of the ground imagery. The kitchen element has a muted, pastel, and geometric construction; it has an obvious generic feel to it, and was appropriated from interior décor magazines. In contrast, the ground image is high saturated, and where it meets the edge of the kitchen furniture, the tension is most high. The ground almost seems to float, to somehow rise above itself, which thus denies the image of any sort of natural grounding. What seems to ground the image, instead, is the earthy tones of the kitchen walls and cabinets, flipping the usual perspective upside-down.

ontrast between the tones and textures of the two main elements of this work: the structure of the kitchen and the organics of the ground imagery. The kitchen element has a muted, pastel, and geometric construction; it has an obvious generic feel to it, and was appropriated from interior décor magazines. In contrast, the ground image is high saturated, and where it meets the edge of the kitchen furniture, the tension is most high. The ground almost seems to float, to somehow rise above itself, which thus denies the image of any sort of natural grounding. What seems to ground the image, instead, is the earthy tones of the kitchen walls and cabinets, flipping the usual perspective upside-down.

Moylan’s work, when contextualized, can be seen as an extension of the artistic practice of cultural critique as exemplified by the work of Bjørn Melhus and Martha Rosler. However, for the artist, the work is highly personal and diaristic. He states that his work is about his life, and that it is for others whatever they bring to the work. When critically examining the work visually, one can see that he in fact uses the very methods by which Rosler’s works succeed in igniting a critique on media and cultural representation. As I have previously elaborated, the subversion of familiarized structures, such as the facialized structure employed by news anchors and politicians, as appropriated by Melhus, and the domestic structures employed by Rosler in her photomontages, are a highly effective method by which one can then reconstruct fragments of mass culture and transmit that reordered information in an accessible way. The audience has been conditioned to understand these structures, and can therefore enter into the work from that point, to then receive the message created by the reconstructed cultural snippets. The process by which Moylan creates his work validates this claim by demonstrating that in the construction of his images, which adhere to the same principles, is achieved through the very method by which the audience will receive them.

In fact, it is interesting to note that Kenneth Moylan cites the recent collage work of John Stezaker as his inspiration to begin working in this way. Stezaker’s work is highly simplified and direct; he is interested in the facialized structure of the portrait, and the visage as window. In his collages, he takes classic portraits, and simply places postcards directly over the face of the disembodied figure. This is useful to note that Moylan’s interest was sparked by works that also seem to fit nicely into this theory of familiarized structure subversion as house for reconstructed cultural fragments.

In fact, it is interesting to note that Kenneth Moylan cites the recent collage work of John Stezaker as his inspiration to begin working in this way. Stezaker’s work is highly simplified and direct; he is interested in the facialized structure of the portrait, and the visage as window. In his collages, he takes classic portraits, and simply places postcards directly over the face of the disembodied figure. This is useful to note that Moylan’s interest was sparked by works that also seem to fit nicely into this theory of familiarized structure subversion as house for reconstructed cultural fragments.

The practice of subversion of the mainstream culture as an artistic method to initiate introspective critique within the art going public is employed by a variety of artists. The work of Bjørn Melhus, Martha Rosler, and Kenneth Moylan, while aesthetically very different, offer great examples as to how artists can and have been successful in creating deep tension regarding our understanding the normalities of our Western reality. The creative critique of mass culture allows the audience to find a comfortable way to begin to deconstruct the implications of their own position in the world, as well as to have the ability to identify, and therefore not be mindlessly persuaded by, the rhetoric of the mainstream.

Notes

1. Mark B. N. Hansen, New Philosophy for New Media (Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2004), 129.

2. Manon Slome, “Aesthetics of Terror (Part 1),” ART LIES: A Contemporary Art Quarterly, 62 (2009), http://www.artlies.org/article.php?id=1760&issue=62&s=0 .

3. Martha Rosler, Decoys and Disruptions: selected writings, 1975-2001 (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2004), 353.

4. Martha Rosler, Decoys and Disruptions: selected writings, 1975-2001 (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2004), 7.

5. Laura Cottingham, “The War is Always Home: Martha Rosler,” New York City (catalogue essay) October 1991, sourced from Martha Rosler’s official site: http://home.earthlink.net/~navva/reviews/cottingham.html .

6. Laura Cottingham, “The War is Always Home: Martha Rosler,” New York City (catalogue essay) October 1991, sourced from Martha Rosler’s official site: http://home.earthlink.net/~navva/reviews/cottingham.html .

7. Martha Rosler, Decoys and Disruptions: selected writings, 1975-2001 (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2004), 355.

8. Alexander Alberro, “The Dialectics of Everyday Life,” in Martha Rosler: Positions in the Life World, ed. Catherine de Zegher (Massachusets: The MIT Press, 1999), 80.

9. Kenneth Moylan, telephone conversation with author, December 5, 2009.

Bibliography

Burnett, Ron, How Images Think. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2004.

Cottingham, Laura, “The War is Always Home: Martha Rosler,” New York City (catalogue essay) October 1991, sourced from Martha Rosler’s official site: http://home.earthlink.net/~navva/reviews/cottingham.html .

Deleuze, Gilles, Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Translated by Hug Tomlinson and Robert Galeta. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

De Zegher, Catherine, ed. Martha Rosler: Positions in the Life World. Chicago: Massachusets: The MIT Press, 1999.

Melhus, Bjørn, Bjørn Melhus: Auto Center Drive. Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag GmbH & Co.KG, 2005.

Palmer, Donald D., Structuralism and Poststructuralism for Beginners. Hanover: Steerforth Press, 2007.

Richardson, Joanne, ed. Anarchitexts: Voices from the Global Digital Resistance. Autonomedia, 2004.

Rosler, Martha, Decoys and Disruptions: selected writings, 1975-2001. Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2004.

Slome, Manon et al. “Aesthetics of Terror (Part 1).” ART LIES: A Contemporary Art Quarterly, 62 (2009), http://www.artlies.org/article.php?id=1760&issue=62&s=0 .

And just for fun, a super negative and awesome critique of Rosler’s work! ::

Saltz, Jerry, “Welcome to the ‘60s, yet Again.” Aesthetica: The Arts and Culture Magazine, http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/saltz/saltz10-14-08.asp .

Kenneth Moylan Wikipedia Page (as linked above)

Interview with Kenneth Moylan: part one, two, and three

More Kenneth Moylan Images:

No comments:

Post a Comment